Our History

Q: Where did the idea come from?

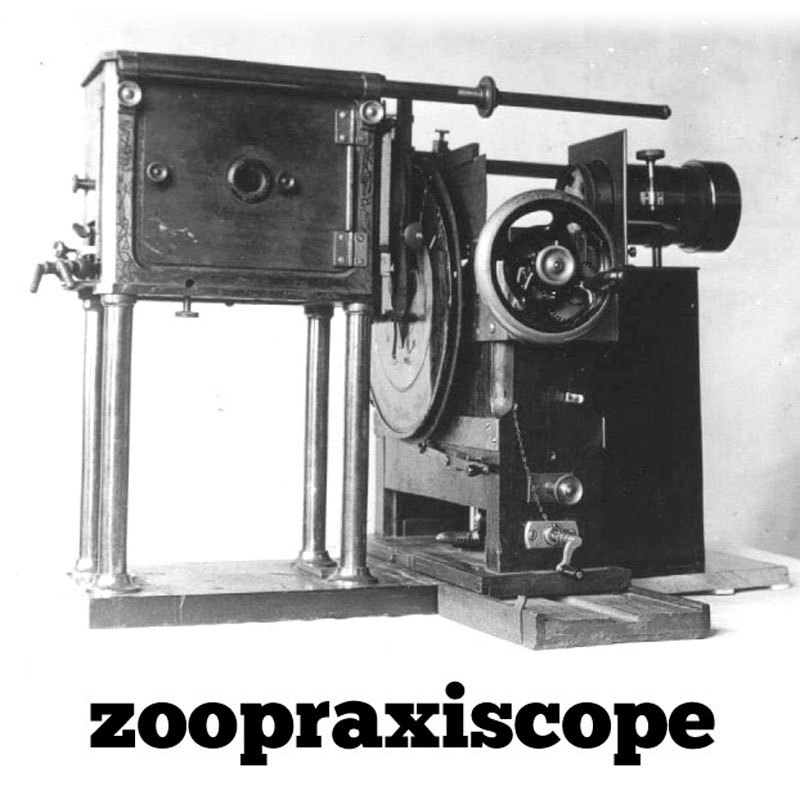

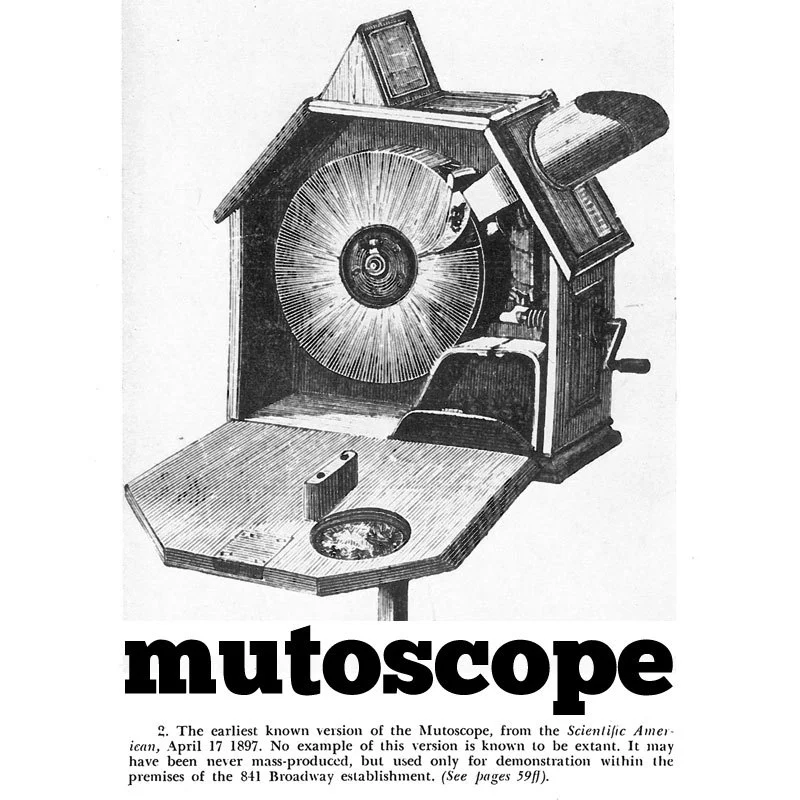

A: (Wendy) In November 2010 I saw a retrospective of Edweard Muybridge at the Tate in London. Having owned a few books of his books in art school as reference for my drawings, I was excited to see his original photographic plates for the motion studies. Muybridge’s images were beautiful, but what I was most amazed to see was his zoopraxiscope (the first movie projector). The device was made from images projected onto rotating glass discs and I began to wonder what a rotating flip book would look like. It brought to mind the penny arcades I visited at amusement parks. They featured the Mutoscope, a hand cranked machine that used a central rotating cylinder with images aligned on the pages. Talking with Mark, we wondered if we could make something compact and more more accessible. Kind of like the introduction of microcomputers to consumers in the 1980’s.

A: (Mark) My first interest was in creating some kind of kinetic electronic art without using LEDs. When we started talking about building flip books, I was thinking bigger and was interested in hacking an old train station sign (split-flip design). After having no luck searching the web (ebay etc.), I knew we could design our own version and add position sensors and a micro-controller to make it more engaging. The first idea was to produce it strictly from scrapped ink-jet printers. Re-purposing obsolete machines has always interested me, and that’s how we created our first flipbook called “birdhouse”.

Q: How does your previous work influence these pieces?

A: (Wendy) My educational background is a BA in Illustration from the University of Buffalo. For the past 15 years I’ve co-owned a company called Slenderfungus that creates digital content for music artists. I love my job because I get to play with photography and video all day. And having the ability to decipher verbose imagery into an abridged narrative is extremely useful when creating flip book imagery. Our flip books usually require that I fit a scenario into 24 frames and that happens in less than 4 seconds. That’s not a lot of time to show an action much less tell a story!

A: (Mark) A 49-year old guy looking back…

Both of may parents were physicists working in high-tech (mostly aerospace) during a time when Southern California was dotted with many aerospace companies like TRW, Rocketdyne, Hughes etc. My experience of Los Angeles is one of wonder, and is somewhat unique. My father had a laboratory that had to be far away from the electromagnetic noise of the city so he could test instruments for measuring tiny spacecraft discharges and subtle magnetic fields in space. This laboratory was nestled in the Malibu hills near the beach. As kids, visiting this lab was amazing. We were naturally taken with the wildlife and creek-life and fauna but the real magic lay in the metal barracks filled with gadgets, liquid hydrogen tanks, test equipment and a giant erector-set gantry for holding NASA satellites to be tested. This was a awesome wonderland to my young eyes, and to this day I still have a sense of nostalgia when I see vintage aerospace equipment.

At the age of 21 I left art school early to start a family. The journey that life took me on was wondrous, but for most of the time, my 30-year vocational path did not feel like the path of an artist dedicated to creativity. I worked as a prop-maker, architectural model builder, electronics test technician, creative director, industrial designer, freelance designer, and invention fabricator. When my daughters grew up and left home for university, I had quite a bit of pent-up creative energy, a few drawers filled with sketches of things I’d build if I had the time, and a super artistic new partner in Wendy. That turned out to be a magical mix of ingredients to rekindle my artistic identity. We started collaborating about 4 years ago.

Q: What are each of your responsibilities during collaboration?

A: (Wendy) Mark is responsible for the mechanics. These little boxes are incredibly complex and making them work is Mark’s field of expertise. He’s my mad scientist sans hubris. Having backgrounds in electronics, fabricating and design, he also doesn’t mind getting grease under his nails. Many of the parts in our flip books are hand tooled so Mark knows his way around the machine shop. He’s been schooling me on welding and using the vertical mill, but I like all my fingers so I try to spend as little time on the bigger machines as possible.

I’m responsible for developing the imagery. In deference to the man who inspired this artistic direction, we decided to embrace Muybridge’s imagery for our first series. Combining his motion studies with our own imagery, we’ve developed a surreal narrative.

My favorite part of our collaboration are in the sculptural aesthetics of the pieces. Figuring out the housing of the flip books is great fun. Many times we plan field trips to aerospace junkyards, abandoned homesteads or dumpster dive here in Venice Beach to find new bits and pieces to create the next artwork.

A: (Mark) Even though we discuss all aspects of a new piece as a team, once production starts we retreat into our own worlds.

Wendy takes on the image production and flip-book page-making; I go to my work-bench to come up with some kind of sculptural housing for the piece and all the mechanical and electronic planning.

Our search for rarefied matter takes us to aerospace graveyards off the beaten path in the San Fernando Valley. Foraging through warehouse racks piled high with dusty old instruments, we often wish we had an old-timer with us that knew the stories behind each of these weird treasures.

Q: How do you decide on the subject matter to animate?

A: (Wendy) We both agreed from the outset that innocence was key to our flip book experience. Being able to bring out the wonder in our viewers was paramount. Our greatest satisfaction is in seeing someone’s face transform in childlike surprise with a giggle or clap of their hands.

A: (Mark) This is where most of our artistic tension takes place too. As a couple, we don’t always agree. The same applies for how an art piece should look or the imagery that it reveals. The one thing we do agree on is: implicitly, there should be a sense of curiosity and nostalgia in each fluttering mechanism that tickles our innocence. Sometimes the viewer has to look twice to find the story, but in the end we’d like to elicit an emotion like surprise or wonder. And kinetic sculpture has a unique appeal. Whether it is hypnotic changing shapes or a harkening of our humanity through gesture, it is an art form like dance, that moves us through the language of motion.

Q: What goes into making a FlipBook?

A: (Wendy) We started developing the plans for these after my trip to London at the end of 2010. When I explained my experience, Mark’s brain started to whir. He knew intuitively how to bring this idea forward from an idea into a working mechanism. He spent the next three months figuring out the inside mechanics, building a few versions before finding the the first prototype he was happy with. Mark is tenacious like that:) Our first piece was called “Birdhouse” and wasn’t completed until six months after the initial idea. We exhibited at the Venice art walk last summer and someone bought it before it was finished. It was taken away so quickly that we didn’t have a chance to enjoy it ourselves! After that purchase we vowed to finish the series before showing these in public again. At that point we started formulating a repeatable design.

A: (Mark) The mechanisms are tricky. I had experimented with many types of motors before I could find one that moved and sounded just right and stripping down ink-jet printers didn’t yield a consistent enough collection of components to adopt that as our path.

I still like the ink-jet approach because of the huge availability of scrapped ones. Every university has a ton of abandoned ink-jets to claim when people graduate or leave for summer break.

Our flipbooks consist of a spindle, pages, a page-restraint bar (that accomplishes the flipping) a gear or belt, a motor, a switch and battery power. The more complex ones also have an arduino, motor and position sensors and sensor/motor-driver circuit. The spindles and mostly hand-machined, but some of the components I was able to mill on our hackerspace’s CNC Mill – saving me hours of tedious drilling.

The flip-book pages are a technical wonder just because of the amount of effort we put into perfecting the process. This is one of the areas where Wendy’s experience with mixed media really produced special results. They are vintage-looking, but are amazingly durable and just the right rigidity to flip gently and so far none have frayed or worn out.